Even though malware code is always evolving and Emotet has morphed from a banking trojan to weapon that targets many industries, email still remains one of the most popular attack vectors for hackers. Phishing attacks are on the rise, spear phishing is becoming more targeted, and now text messages are turning into spam.

The following advice from security experts will help tech pros spot new attacks, improve their technical defenses, and train end users and tech team members.

Strengthening the perimeter

Ron Culler, senior director of technology and solutions at ADT cyber security, said that in addition to the standard anti-virus and anti-malware tools, businesses should use sandboxing technology to screen email traffic for malicious code embedded in HTML or in attachments.

“Sandboxes emulate desktop environments so when a message comes in with attachment, it goes through the process and simulates the entire process so you can see if something happens maliciously,” he said.

Companies also should run phishing drills in-house with email templates that look professional and include persuasive language. “You send emails to people, and if they click the link, it could tell them, ‘You’ve clicked a phishing link, go here for training,'” Culler said.

Trends in business email compromise attacks

Although email attacks remain the most common delivery method for malware, text messaging follows at a close second as hackers increase their use of deceptive text messages.

David Richardson, vice president of product at Lookout, said that bad actors are now building sites specifically targeting mobile devices. Some of these sites will redirect users to a genuine site if a link is being examined on the desktop or through automated analysis.

“Bad actors are realizing that they can keep their sites undetected for longer by redirecting to the actual site in some circumstances because that will mark them as legitimate,” he said.

Richardson added that many of these attacks come from compromised accounts from mobile apps, such as What’s App.

“Hackers will compromise someone’s account and then send this message to everyone in their address book, and people will click because it looks legitimate,” he said.

Bad actors also trick users by closely copying the layout of trusted brand’s login page. The page looks right but often the log-in and password fields are on one page, instead of separate screens. “Attackers put all the content on a single page to keep things more focused there instead of breaking it up into a multi-step process,” he said.

Users should also look for pixelated logos, poor grammar, or awkward writing as warning signs of a phishing page.

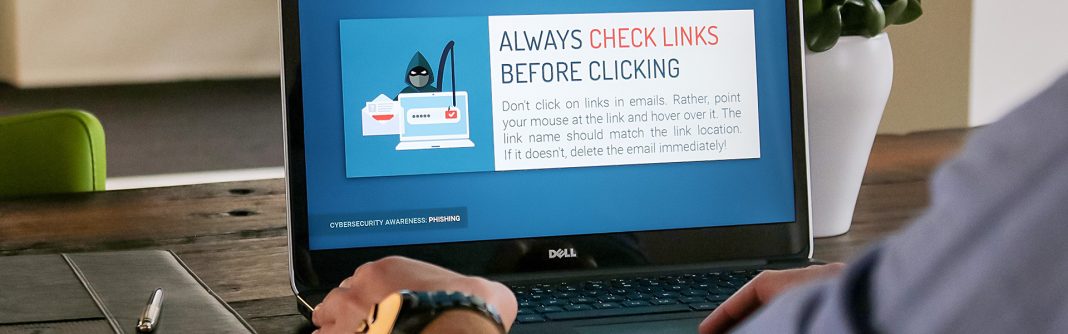

Another common trick is to make the full URL hard to see because of the limited real estate on a mobile screen. Culler from ADT recommended telling users to hover a mouse over a button or URL to check where a link is going.

Screen overlay attacks is another popular approach. This is where hackers embed malicious code in something that seems innocent, like a flashlight app. The malicious code tracks what the user is doing and looks for specific activity. When a user taps on a banking app, for example, the malicious code launches a full screen popup that mimics the genuine app. This gives the bad actor the chance to capture user information without redirecting the person to a website.

“You’ve switched context from one app to another and provided personal information to an attacker without realizing it,” Richardson said. “Then it will basically dismiss that application and switch you back to the normal app.”

Richardson said companies need a device management strategy that monitors activity and controls access in real-time.

“If you are an enterprise trying to manage 10,000 devices, what are the odds that your users are going to use good judgement all the time?” he said.

Michael Bruemmer from Experian said he has seen people use fake LinkedIn profiles to try to steal a person’s credentials. He said hackers will scan social media to identify a person’s interests and use that information to personalize the phishing attack.

“They know that I am a bike rider so they use that information to send a targeted attack through text or email, ‘Click to see the pictures from the ride last weekend,” he said.

Preventing business email compromise attacks

Bruemmer said that companies should conduct job-specific security and privacy training at least once a year. The training should reflect a person’s job responsibilities and role within the company.

“Admins, the CEO, and board members need the highest level of training because they are under attack all the time,” he said. “The front desk security guard needs a different type of training, but everyone needs it.”

Companies also need to practice responding to a data breach, if — or more likely when — a phishing attack is successful. Bruemmer recommended assembling a cross-functional group that includes the IT security team lead, the chief privacy officer, a representative from the corporate board, internal security experts, and potentially a breach coach and outside legal counsel as well.

“It’s a large number of people who need to be coordinated, and it takes time and practice to get that group together,” he said. “Everything looks good on paper, but unless you practice, then a breach hits and chaos ensues.”

He added that company leaders often overlook the fact that the response team will need to be dedicated full time to the problem until it is resolved.

“The rest of the business has to continue at the same time, but people can’t be pulled in and out of the response work,” he said.

His other piece of advice for the response team is to plan for leaks.

“We’ve got this plan and 30 or 60 days to respond to the consumer, but if you are preempted before you are ready to go what are you going to do?” he said.